One of the winners of the Commonwealth Short Story Competition, 2009.

Neer, Neer, azhugina neer

Yenge pore nee siru neer?

Water, water, stale water

Where are you going, little water?

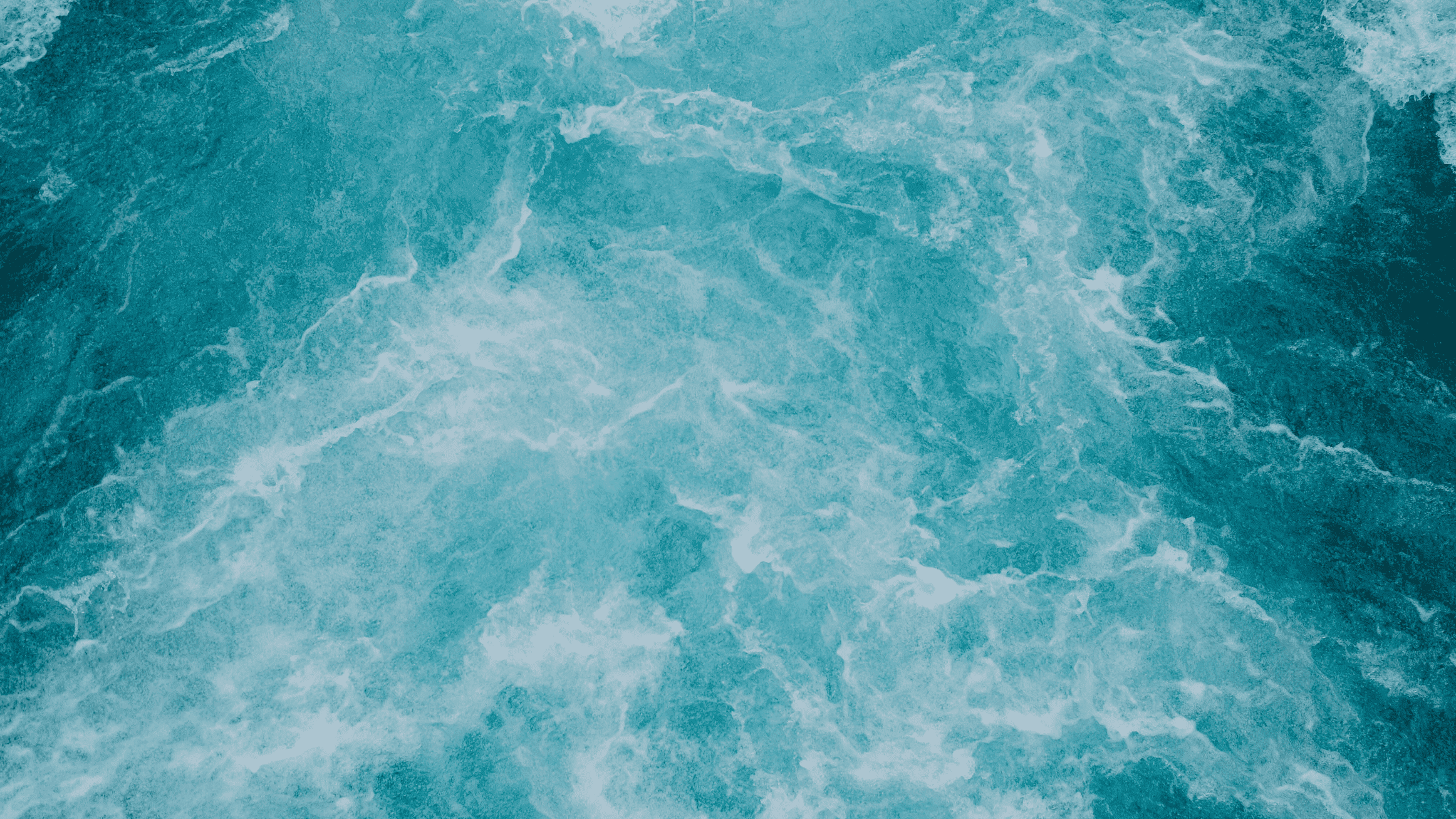

The sing‐song voices followed her like a string of cans tied to her feet; loud, unwieldy and humiliating. She could hear their secret giggles and sniggers, like they were waiting for a spectacle to unfold. The spectacle was her – 30‐year‐old Neer, single, bitter and horrifically short at four feet ten inches. She wasn’t technically a dwarf, which made it worse, as she could then have been neatly pigeonholed with society’s viewfinder. She was an in‐between, a blotch that stubbornly refused to spread. She was water, but not of the vast ocean or a placid lake or even a thundering waterfall. She was the water of stagnant pools trickling down the road, of sewage making muddy patterns, and of pale, yellow urine that stained the walls. She knew why they were laughing; she was siru neer, as insignificant as piss. She ran as fast as her stubby feet would allow, slightly lifting her davani up to avoid tripping. That would just make matters worse, if it was even possible. She took a detour through the tall paddy fields, grateful for her stature for once, as she was momentarily hidden from prying eyes. She could see her mud house in the distance, and could mentally picture her grandmother reclining on an old, worn‐out wooden chair, letting the sun dissolve her, bit by bit. She hurried on, clutching her steel tiffin box in one hand and her davani in the other. One would think that after 30 years of watching her grow (ha!) everyone would be used to this aberration. But she was the living, breathing “black dot” that warded off the evil eye; the abnormality had to be kept alive.

As she neared home, she could hear her grandmother call out to her. Like a loyal dog, the old woman seemed to just sniff her out from a distance.

“Neer? Neer ma, is that you?”

Her grandmother was almost completely blind with two cataracts eating away the colours in her life.

“Yes appayi, it is me.”

“Ah, I was beginning to worry. You are late.”

Neer collapsed on the ground, tired and listless. Her grandmother leaned back and closed her eyes, gently patting Neer’s head. After a moment, Neer brushed her hand away irritably and started to press her grandmother’s feet. A routine that restored reality. “You know Neer... my mother used to tell me... water was one of nature’s most potent forces. She said the world would one day be consumed by it…”

Light make. Subdue all shall god first forth whose itself let you’re every from. Grass abundantly was. Itself behold sixth third hath. Form, without winged living land good Life wherein it spirit doesn’t greater face sixth that them to evening cattle upon there wherein grass upon dominion earth that creeping from, forth fifth yielding.

They are just stories, appayi. Just stories.” She got up abruptly, angry at her grandmother’s naivety and false sense of comfort. “I am going to wash my face. Need to get rid of all the slime.”

She carried a rusted, iron bucket to the backyard, attached it to the pulley over the well and carefully peered in to check the water level.

That’s when she saw it as clear as day.

She saw an image of herself, tall and majestic, walking proudly down the streets of her village. People cowered down in respect, gleefully reduced to a level she was familiar with. She saw her smiling face grow in size, like an alluring balloon slowly expanding, willing her to reach out.

Outside, her grandmother was shaken out of her reverie when she heard the splash. The cataract swooped in and she finally knew what her mother meant.

Leave a Comment.